The purpose-free organization

An organization’s main purpose is to give its members a certain social status. Whether employees do productive work or bullshit jobs makes no difference in the life of the organization.1 Other theories, which state that organizations exist to achieve a specific goal, fail to explain how so many of them can still smoothly obtain resources and pay salaries while being totally dysfunctional (the kind of organizations whose own employees tell you “I don’t understand how it can still run!”).2

Based on this assumption (organizations exist to provide status), it becomes normal that an organization can function without a purpose, without any work being done. The more interesting question becomes: Under which circumstances can one do productive work? How can employees escape their bullshit job?

In 2006, I was a volunteer in an Israeli kibbutz in the Negev desert. The kibbutzim (plural of kibbutz) were collective farms created in the first half of the 20th century by socialist and communists emigrants to Palestine. On the kibbutz, all members were supposedly equal. But the families of the kibbutz’s founders were way more equal than the rest. They had the best houses, they didn’t have to participate in the daily chores and commuted by car to the big city nearby. Others, such as more recent, non-white emigrants, volunteers and garin soldiers (conscripts with no family in Israel), did most of the work. While the principles of kibbutz life were still respected (there was a common meal on Friday night, money was prohibited), few were stupid enough to believe that they were living the real thing.

A kibbutz member who had lived there long enough told me that things started to go downhill for kibbutzim in the 1970s, “when the swimming pools were built.” Swimming pools were much more than concrete basins painted blue and filled with water. They were the symbol of the victory over the desert, of the success of the irrigation plans that provided Israel with food security. With the swimming pools, the kibbutzim’s mission was over.3

The kibbutzim did not disappear with their mission. But from thriving communes where everyone was equal, they became purpose-less organizations, concerned only with maintaining the social status of their members, even if it meant reneging on their fundamental principles.4

Mission statements

Kibbutzim lost their purpose in the 1970s because the goal they had set for themselves, to become prosperous communities in a secure Israel, had been met. They did not have an additional goal to keep the movement going, so they started unraveling.

The mission, or purpose, of an organization, is a tangible goal which members are asked to achieve. It can be fixed (e.g. “bring electricity to every house in the country” was the goal of national electric utilities in the second half of the 20th century) or continuous (e.g. “provide affordable energy in a sustainable way” could have been the goal of these utilities afterwards).

Having a clear mission is important, it keeps employees motivated. But it goes beyond mere motivation. Only with a goal that all members of an organization agree on can work be assessed: Anyone can see if a task contributes to the completion of the overarching mission.

To see the concept in action, look no further than a national army engaged in a war (provided the government issued clear war goals, e.g. “conquer a given territory”). There, any action or innovation that contributes to winning the war can be identified (e.g. because it kills more enemies or reduces losses) and rewarded. Trust emerges between colleagues because a joint endeavor can result in joint rewards.5

If an organization has no mission, no work can be done to progress towards a common goal (there is no goal). Productive work on smaller projects (which might have been created with a goal in mind) within the organization can still be done but it will not be rewarded, as there is no way of telling a good project from a useless one.

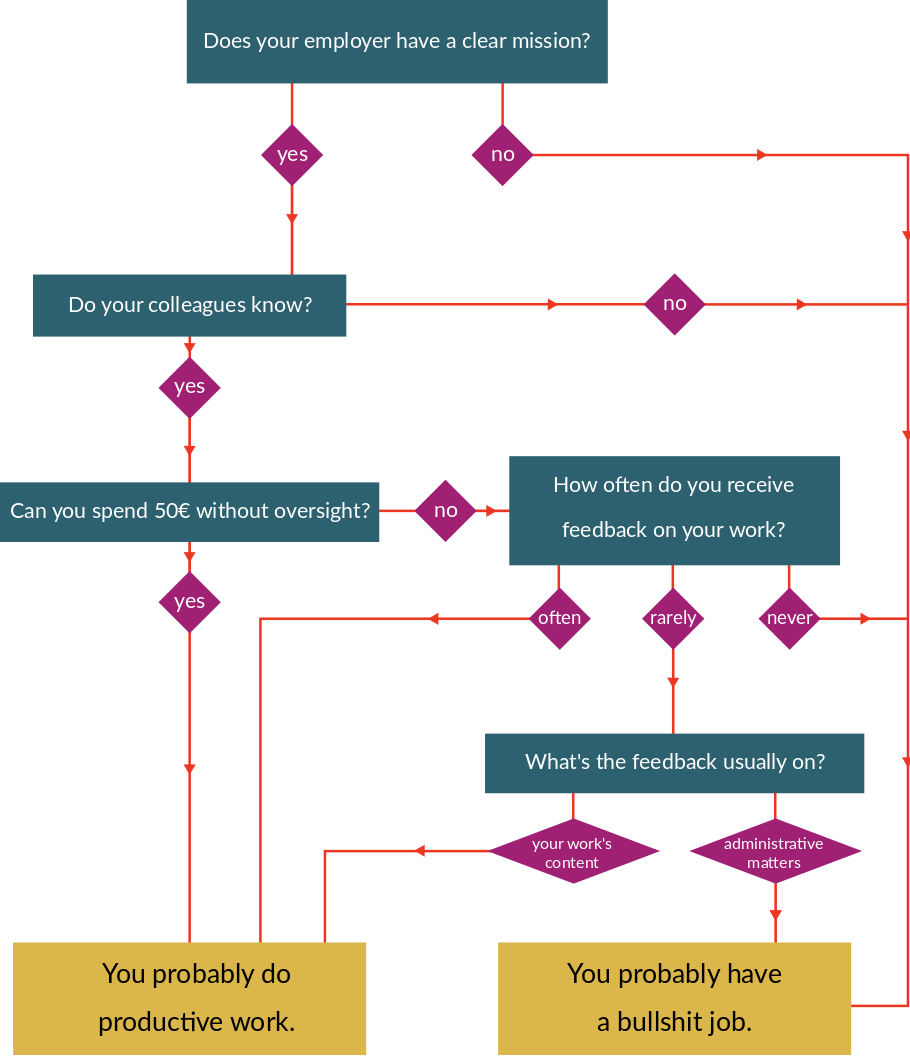

Do you have a bullshit job?

Management through fear

In an organization that has a mission, hierarchy reflects past achievements or an ability to manage others efficiently towards the organization’s goal. Without a mission, hierarchy only reflects power relationships between individuals. Management is based on personal loyalty, not productive work. Loyalty might include an obligation to provide resources to the organization, just like a mafia underling is required both to obey the boss and to bring in money.6

When there is no goal to positively assess someone’s actions positive feedback is impossible, so that negative feedback is the only tool available to enforce hierarchy. Feedback can only be punitive and, as a result, fear of retaliation becomes the norm. The European Commission offers numerous examples of management through fear. It happened that I handed in lengthy (and solid!) reports, only to receive comments on how the EC logo was placed on the front page. The contents of the work were irrelevant because all knew that the only possible feedback from higher-ups was negative.

Without the possibility of positive feedback, trust is impossible because an association between colleagues to do productive work will not be rewarded. If A knows that B’s work will produce the same outcome within the organization whether it is good or bad, A has no interest in helping B produce better work, for B will get nothing from A’s help and have nothing to give back to A.7

In an army at war, soldiers are usually promoted after a feat of heroism on the battlefield (hierarchy reflects past achievements). In an army engaged in wars that have no goals (e.g. the war on terror) or at peace, soldiers are promoted following personal allegiances rather than actual deeds.8 The existence or absence of a mission defines how an organization is managed.

Knowing whether or not an organization has a mission is surprisingly easy. If you doubt that it has one, it probably does not. If two people within the organization come up with vastly different answers, it probably does not. If it places faith in arbitrary numerical indicators to describe individual performance, it probably does not. If the official mission statement is bullshit9 (a mix of English and native words is a red flag), it definitely does not.

“Creating value for shareholders” is not a mission, it is simply the signal that the fruits of one’s work will be given to someone else. Franchised chains, where workers are explicitly excluded from the business’ core mission, which is managed by the brand-owning company, are salient examples of purpose-less organizations. “Making enough money to pay salaries” cannot be a mission for, as I wrote in the first line of this essay, it is the foundation of any organization.

Losing it

The loss of a mission can occur in two ways.

The mission can be accomplished. This was the case for the kibbutzim and for successful armies. It was the case for Facebook which, in the past few years, successfully linked together all computer-owning humans. Unsurprisingly, relationships between employees at Facebook are since based on fear and personal loyalty, as several journalistic investigations showed in the past few months.10

The mission, though not accomplished, can also be altered to the point of irrelevance. A web start-up company that aimed at world dominance, reached profitability but failed to become market leader falls in this category (start-ups are never built to become mid-sized businesses). So, too, do many public services that have been transformed to mimic the private sector. Universities, for instance, were built to protect and research the truth and have been transformed into providers of human capital.11 The European Commission is another good example. Created to rule above the member states of the European Union, it has since the early 2010s become their secretariat, renouncing its original mission.12 Hospitals which went from curing patients to extracting money from customers, pharmaceutical companies which market addictive drugs instead of cures and appliance makers which design products to fail rapidly (built-in obsolescence) are all without missions.

Having a mission is not enough in itself. An army might have a clear war objective ; if it is being routed by enemy forces, any productive work done by soldiers or supporting staff will still lead to nothing. To exist, productive work requires growth.

Growth

If your organization does not grow, any reward to your colleagues mechanically means that you, or someone else, will get less. When any personal progress is made at the expense of others, generalized mistrust is the result. Every member of the organization must be careful not to be overrun by an ambitious colleague.

Trust between members becomes impossible because A will always have a good reason to believe that any help given to B will never be paid back. Instead, B has an incentive to extract as much as possible from A, for there is no other way to progress within the organization. Duplicity and back-stabbing become everyday occurrences. Productive work is impossible because if B believes that A might be rewarded for a task well made, B will have a good reason to torpedo A’s work (otherwise, A risks being rewarded at the expense of B). A knows that and, as a results, refrains from doing productive work. When there is no growth, embracing bullshit jobs becomes a survival strategy.

Growth occurs in two ways. An organization might increase its power, by gaining command over more resources or by convincing others that its resources are more valuable. This is what most people think of as “growth”. It translates in more sales, by volume or by value, and in more assets.

Another path to growth opens when less humans are around to share a given capital. Destruction of life, provided that factories, fields and equipment remain intact, offers great perspectives to those who survive. Epidemics that kill randomly (so that people at all hierarchical levels disappear) or random purges have historically provided fantastic career opportunities to people who previously stood no chance because of their low social status.13

Growth is only important insofar as members of the organization can benefit from it. The bottom line of a company may increase ; if all the profits are directed to a third party (the state or shareholders), the organization behaves as if it were not growing at all. Expectation of possible personal advancement better describes what I mean by growth, but “growth” has the advantage of brevity.

Four types of organizations

From the two binary variables exposed above, organizations can be divided in four groups.

No mission - No growth

In the absence of growth, any work that is considered productive is a potential threat for all others. By engaging in productive work and being good at it, an employee further shows that she could apply her skills somewhere else and therefore, that she has less to lose from a challenge within the organization than someone mediocre. In a stagnating organization that has no mission, people engaging in productive work are never promoted and often fired.14

Without a mission and without growth, relationships between colleagues are based on mistrust and hierarchical links are based on fear.

You can quickly assess the level of fear of your own organization with this simple test. If the resources your organization puts in preventing you from buying something (because several people need to approve your buying office supplies, say, or a train ticket) is more than double the price of the item you wanted to buy, fear overweights any sense of purpose.

Such organizations do not necessarily crumble. They still provide status to their members so that, even if fear becomes an everyday experience, even if work is constantly sabotaged, one is better in than out. For the overwhelming majority of people, doing a bullshit job is better than to be unemployed.

Unfortunately, this type of organization is the default and, except for periods of very high economic growth, the most common. It is the default because, as I show below, is the only stable one.

No mission - Growth

An organization can have no mission and still grow. This can happen because the economic environment is such that it “lifts all the boats”. Any organization that is so large that it suffers little from competition (that includes all public services and much of the corporate world) will benefit from a growing economy, even if it does not do anything productive.

In this context, the absence of a mission makes positive feedback impossible, so that productive work is not rewarded and fear still dominates. However, as long as the organization grows, productive work is not seen as a threat. Anyone who wishes to do something other than a bullshit job is free to do so.

This configuration lasts only as long as growth. Because productive work is not rewarded, the organization cannot grow by taking market share from its competitors - any growth must come from outside. As soon as growth stop, the organization reverses to the default state (no mission - no growth) and anyone engaging in productive work is either fired or leaves by themselves.

When employees are offered a bail-out to leave their company, a strong signal that the organization is shrinking, it is often the best among them who take it. They might have other professional plans, they are also the ones who know that they will not be able to perform a bullshit job if they stay.

Mission - No growth

An organization might have a clear mission but, like a retreating army, offer no opportunities to its members. In the words of Winston Churchill, they have “nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat”. This is probably the most unstable type of organization. Either members of the organization can regroup around the mission statement and turn the tide, starting growth anew, or they can give up on the organization’s mission and enter the stable state of “no mission - no growth”.

Turning the tide is only possible for organizations that acquire their resources themselves. If growth depends on a third party, as is the case for all public services, a return to growth is impossible.

You can witness the shift from growth to contraction in much of the public sector. In state-funded public education, for instance, teachers who care about their mission and try to innovate in the classroom are systematically punished, even when their work is appreciated by pupils and parents. In health care systems that are being shrunk (that means, in Europe at least, most of them), personnel who consider their occupation to be a bullshit job have a great advantage over those who care about patients, for they are not at risk of burning out.

Private sector firms also routinely renounce their mission when growth runs out. It is vastly more comfortable for decision-makers to abandon a mission rather than to jeopardize the value of the company’s shares at the stock exchange. The example of Facebook, mentioned above, is a case in point where a company remorselessly gives up on its mission in order to enjoy the benefits of the position it acquired. Google’s dropping its “don’t be evil” motto in October 2015 was also a sign of its renouncement to its original mission.15

Mission - Growth

When an organization has a clear goal and provides new opportunities to all members through growth, productive work is sought and rewarded. Bullshit jobs do not exist because anyone not contributing to the organization’s goals risks being fired or, at least, not promoted. While some members might free-ride on the others’ work, trust between employees is the norm as everyone knows that better work will translate in better opportunities for all.

Most newly-created organizations enter this category, even if the growth is short-lived. In times of economic growth, any organization with a mission does, too. In times of stagnation, in which we find ourselves in since the late 2000s in Europe, such organizations are the exception.

Extending the theory

I started thinking about this theory to explain my own experiences working with or within some organizations. But its potential goes beyond my own work history. For instance, it explains why the same occupation (e.g. marketing director) can be a bullshit job in one organization and a fulfilling one in another.

If you extend the theory to society at large, assuming it can be considered one organization, it also explains why so many innovations happen in war time. It’s not that nationalism makes people smarter, or that the necessities of war force people to think in new ways. It’s simply that in war, there is a clear goal against which a job can be measured, which in turns allows for rewarding productive work. (And because many people die in war, there are plenty of career opportunities for who engages in productive work.)

The theory also fits nicely with the work of David Herlihy in The Black Death and the Transformation of the West, where he argues that the Age of Discovery, from the 15th to the 18th century, was made possible by the numerous plagues that hit Europe. Every forty years or so, a new plague killed one in ten, sometimes more, inhabitants, while leaving capital intact. These were as many opportunities for social promotion, which made productive work possible and led to the spread of the printing press, the compass and the caravel.

Finally, it explains why bullshit jobs rose as the economy stagnated (stagnated in the sense that income of all but the very richest stopped rising despite nominal GDP growth). Without growth, most organizations that had a mission had to jettison it to preserve their social standing, reverting to the first category of the typology above, “no mission - no growth”.

The rise of bullshit jobs has collateral effects. They require that employees accept the irrelevance of their work. They can do so in one of two ways, either by accepting a strong cognitive dissonance between their actions and their judgment, or by switching off critical thinking and accepting their bullshit job and their constant duplicity at work as a good thing.

Switching off critical thinking is obviously much easier, not to mention that cognitive dissonance might lead to psychological problems.16 The disappearance of critical thinking and the spread of dishonesty within organizations transforms the general population, making it easier for untruths to penetrate it and much harder for the truth to gain footing. Truth, which is the first tool needed to do productive work (assessing a task against a mission implies the existence of truth, which is needed to make the judgment), is an obstacle to bullshit jobs. Because truth forces us to think critically, it can prevent loyalty (truth might contradict the person you should be loyal to), which is the cornerstone of management in organizations that have no mission.

It is no coincidence that science is seen positively only in times of high economic growth and considered a nuisance in times of stagnation.

Notes

1. In the context of this essay, productive work is considered the opposite of bullshit jobs. Productive work is done with a goal in mind, it is fulfilling and can be appreciated by peers. While bullshit jobs are obvious for white-collar workers, they exist in other sectors, too. A manual worker whose work involves senseless procedures, or procedures that a built to fail, has a bullshit job. So do farmers that use their land or animals senselessly.

2. I already wrote at length on the topic in Everything we know about price formation is wrong.

3. The 1970s also saw the stabilization of Israel’s military situation after the 1973 Yom Kippur war. Kibbutzim had played a major military role from the 1940s to the 1960s. The end of traditional war between Israel and its neighbors also had an impact on their mission.

4. After hitting a low in the 2000s, the kibbutz movement is experiencing a revival and growing again - though mostly as suburban communities. See After 100 Years, the Kibbutz Movement Has Completely Changed, Haaretz, 3 January 2007, and More Young Families Opt for Communal Life, Haaretz, 3 June 2015.

5. Trust is the acceptance of a personal risk in a joint endeavor, e.g. when A does something for B even though there is no guarantee that it will benefit A in the future. A trusts B to pay it back at a later time. It makes sense for A to help B if A knows that the outcome of B’s work will be rewarded so that B can share the benefits with A or help A at a later time.

6. I wrote at length on the emergence of mafia-like structures when institutions disappear in The emergence of the mafia state.

7. Orthodox organization theory assumes that trust is a cultural trait of an organization (see Richard L. Daft, Organization Theory and Design, 10th Edition, South-Western College Pub, 2009, p.374). I disagree.

8. Alexandre Benalla, for instance, a friend of French president Macron, is a lieutenant colonel (just two ranks short of general) in the reserve army. See Affaire Benalla : que vaut le grade de lieutenant colonel de la réserve citoyenne de la gendarmerie ?, Libération, 20 July 2018.

9. Since Harry Frankfurt’s 2005 essay On Bullshit, bullshit has become an actual term in social science.

10. See Mark Zuckerberg’s Biggest Problem: Internal Tensions At Facebook Are Boiling Over, Buzzfeed News, 5 December 2018, or Inside Facebook’s ‘cult-like’ workplace, where dissent is discouraged and employees pretend to be happy all the time, CNBC, 8 January 2019

11. I wrote on the topic in The collapse of academia.

12. I wrote about it in Why the European Union failed.

13. Note that this does not work if capital and human lives are destroyed at the same rate, or if the humans who disappear belong to the lower social ranks only.

14. Diego Gambetta, an Italian-born sociologist, makes the same argument in Codes of the underworld: How criminals communicate. Princeton University Press, 2011, p. 42-45.

15. Management through fear probably increased at both companies. However, since both continue growing, some employees are still able to carry out productive work.

16. The ‘brain scissors’ of GDR dissidents is a perfect example. See Schere im Kopf, Der Spiegel, January 1 1993.