The colonial roots of French fries

In the second quarter of the 19th century, as the trade in men and women was waning, European merchants started trading in groundnuts off the coast of West Africa.1 In the decades that followed, trade boomed in Marseilles, Liverpool and Hamburg for dried coconuts from Pacific islands, for palm kernels from the Dutch East Indies (current Indonesia), British Nigeria or the Belgian Congo, for cottonseed from Texas or from sesame from British India. All of these commodities were crushed and refined into one final product: fat.

Fat had been scarce in Europe for most people, most of the time. Starting in the late 19th century, it became more and more abundant. It was needed for lamps and lubricating machinery but, as mineral oils became widely available, the use of vegetable fats became more concentrated in soap-making and, what interests me here, food.2

Alone among the major foodstuffs, fats were largely imported. Animal fats were often imported from the Río de la Plata and from the United States, and vegetable fats were almost exclusively imported from colonial situations.3

The abundance of fats in Europe led to dramatic changes. Production and sales of soap skyrocketed. On the food front, it allowed for a massive expansion of deep-frying, which is probably linked with the growing popularity of French fries, Frikadelle and fish-and-chips.4 It also boosted the ice cream industry, which was one of the main buyers of coconut oil in the 1920s.5

I discovered the link between the colonial context in which these vegetable fats were produced and the foodstuffs made from them in Europe while writing Voracism: Three centuries of white supremacy in food (published in 2021). I found it so fascinating that I decided to research it in details for a doctoral thesis, which professor Günther Hirschfelder of Regensburg University very kindly accepted to supervise.

I will spend part of the upcoming years looking at the cultural history of colonial vegetable fats in France and Germany between 1871 (when margarine – a key innovation that lets industrialists merge different fats together – was first produced and Germany unified) until 1933 (when the German government led by the Nazis monopolized the edible fats business). I plan to organize my research along three axes.

A cultural interpretation of prices

The theory of demand and supply has some limitations, and I explored how cultural traits – rather than market forces – could become the main drivers of prices in my upcoming book Full-time imposture (to be published 2022).

When it comes to the price of fats, marginalist economics are of little use. This theory, which became hegemonic in the late 20th century, requires products to have intrinsic qualities. But fats do not. Contemporaries agreed on one thing: it was close to impossible to notice if one was buying butter or margarine. An almost certainly apocryphal story making the rounds in 1890s France was that a margarine had been awarded the top prize at a butter competition.6 In other words, the prices of different fats was determined by cultural factors rather than supply and demand.

Heeding the calls of several food or cultural historians,7 I will study prices as cultural artefacts. In particular, information about the evolution of the price of vegetable fats relative to butter will yield insights on the acceptance of these exotic produce by merchants and by the population.

Another avenue of research will be the abundant literature on fraud, which implicitly reveals the commercial hierarchy of fats (those at the top are often falsified, those at the bottom, never).

The colonial context in advertising strategies

Manufacturers who used colonial vegetable fats (chiefly margarine, coconut butter and groundnut oil) as their main ingredients attempted to influence the perceptions of their wares. A common slogan throughout the period is that a margarine “is worth butter” – its longevity itself a testament to its impotence.

More precisely, I will focus on the representations of colonial subjects in advertising for colonial vegetable fats. Manufacturers, which often sold and marketed soap alongside margarine and oil, were at the forefront of innovation in advertising. Lever Brothers, for instance, spent more than 10% of sales on advertising in the first decade of the 20th century.8 Palmin, taking a hint from Liebig, printed millions of chromolithographic cards between 1903 and 19149. Rama pioneered free brand magazines for children with Der kleine Coco (1909-1915). Often, such advertising used colonial themes.

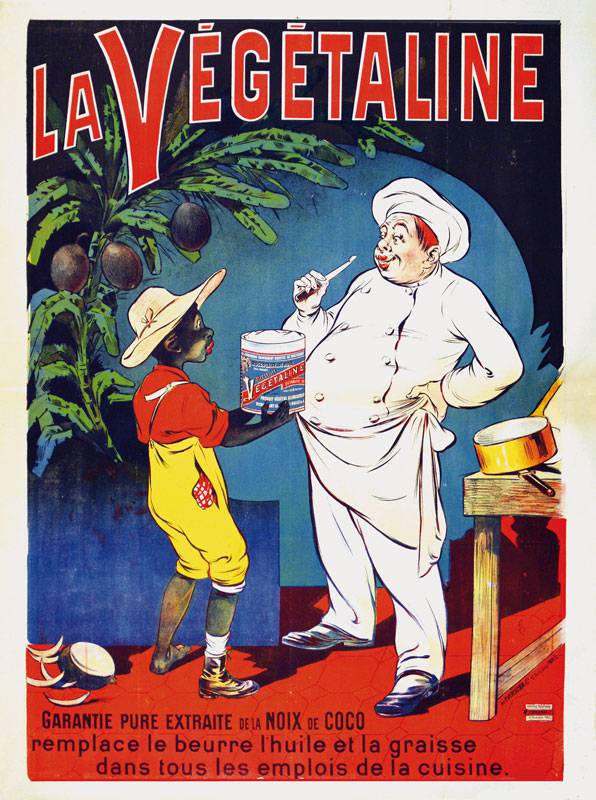

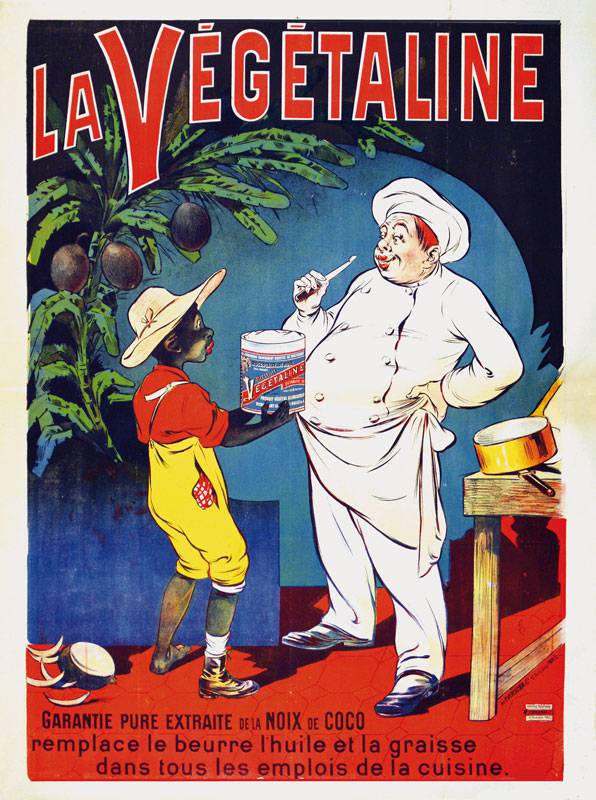

This advertisement for Végétaline (a brand of Rocca, Tassy & de Roux of Marseilles), for instance, uses age-old tropes of racial distinction. The small, Black child is made to enhance the whiteness and the position of the chef. It is likely that the artist, Eugène Ogé, was aware of the long tradition of representing Black servants in front of their mistress.10

Advertisement for Végétaline, 1910.

Advertisement for Végétaline, 1910.

Portrait of Louise de Kérouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth, by Pierre Mignard, 1682.

Portrait of Louise de Kérouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth, by Pierre Mignard, 1682.

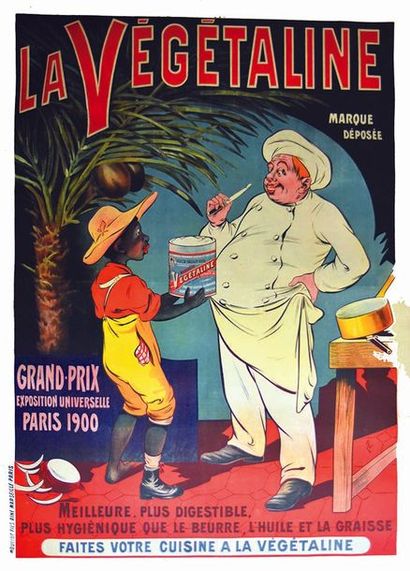

There is much more to this advertisement than a continuation of 17th-century themes, however. Firstly, Végétaline is made of coconuts, as is clear from the drawing. In the early 20th century, coconuts were sourced from the Pacific. Given the very high interest for ethnography at the time, Ogé would have had no scarcity of source material if he had wanted to draw a Melanesian man or woman. Instead, he drew a Black child from the Jim Crow South in the style of US cartoonists. He also chose to represent the coconut tree in the shape of a banana tree with a bamboo stem. Coconut trees look nothing like this and Ogé knew it very well, as this other version of the advert, which is likely older, attests.

Advertisement for Végétaline, around 1910.

Advertisement for Végétaline, around 1910.

Advertisement for Végétaline, around 1900.

Advertisement for Végétaline, around 1900.

The people marketing Végétaline, from the artist to the firm’s management, deliberately created a syncretic Other, merging all possible embodiments of exoticism in the advert. Other brands of colonial vegetable fats made similar choices. Palmin, for instance, used pyramids as its logo.

Given that margarine was a product for the lowest classes, this racial othering might have served to overshadow class differences in favor of racial ones.11 Margarine advertising and consumption might have contributed to turning consumers from working-class poor into powerful whites, in what Kyla Wazana Tompkins called “eating as a racially performative act”.12

The absence of colonial vegetable fats in cookbooks

The third axis of my research program are cookbooks. Scholars have shown that, far from being a collection of unambiguous lists of instructions, cookbooks reveal a lot about the way their authors – and potentially their readers – saw the world.13

I started building a database of word frequencies French and German cookbooks, which currently holds 296 books. Because research is about sharing, I made it available to all online at blog.nkb.fr/cookbooks.

It shows that, despite the immense increase in fat availability in Europe between the mid-19th century and the mid-20th century, cookbook authors did not increase the number of frying recipes. More remarkably, bourgeois cookbooks entirely overlooked colonial vegetable fats and margarine. When they did mention them, it was usually not in praise. “Margarine, cet affreux produit” (this horrendous produce), wrote for instance Paul Friand in 1896.14

Manufacturers, notably H. Schlinck (producer of Palmin, a coconut butter), published their own cookbooks and made them available to households by the thousands. Despite this aggressive push, other authors did not pick up any of their recipes that used coconut butter. There would have been a very good reason to mention it, as anyone who baked with coconut oil knows: the quantity needs to be reduced by 20% compared to butter (and water needs to be added in some recipes).

In some cases, authors ignored these new fats although they (or their publisher) expected their readers to use them. À table chez tante Claire, published in 1929, for instance, does not once mention margarine or coconut butter in the recipes. But among the advertisements it carries, no less than three are for margarine!

I hope this research will shed some light on the links between whiteness and foodstuffs in France and Germany, if they exist. More generally, I hope it will inform research concerning the perception of the origin and production situation of the food we eat today. Many products still depict a generic Other to illustrate their origin on their packaging, even after Mars Foods rebranded its famous parboiled rice.

It goes without saying that I would be very grateful for any piece of advice or literature recommendation! If you are a fellow nerd of cultural food history, do get in touch: hi@nkb.fr.

Notes

1. Brooks, George E. ‘Peanuts and Colonialism: Consequences of the commercialization of peanuts in West Africa, 1830–701.’ The Journal of African History 16.1 (1975): 29-54.

2. Jumelle, Henri. Les huiles végétales : origines, procédés de préparation, caractères et emplois, 1921, p. 68.

3. ‘Colonial situations’ in the sense of Georges Balandier’s definition: Domination by a culturally distinct minority over a technologically inferior indigenous majority in the name of a dogmatically asserted racial and cultural superiority.

4. Walton writes that fish and chips fryers used any fat they could get hold of. Walton, John K. Fish and Chips, and the British Working Class, 1870-1940. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2000, p. 8.

5. Jackman, Harry H. Copra marketing and price stabilisation in Papaua New Guinea: a history to 1975. Canberra, ACT: Development Studies Centre, Research School of Pacfic Studies, The Australian National University, 2017, pp. 39 and 63.

6. ‘Beurre et Margarine’, Le Petit Journal, 13 December 1891.

7. For instance: Applegate, Celia, and Pamela Potter. ‘Cultural History: Where It Has Been and Where It Is Going.’ Central European History 51.1 (2018): 75-82. And: Scholliers, Peter. ‘Twenty-five years of studying un Phènoméne social total: Food history writing on Europe in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.’ Food, Culture & Society 10.3 (2007): 449-471, here p. 467.

8. Jackman, op. cit., p. 10.

9. Ciarlo, David. Advertising Empire: race and visual culture in imperial Germany. Vol. 171. Harvard University Press, 2011, p. 215.

10. For the long tradition: Pieterse, Jan Nederveen. White on black: Images of Africa and blacks in western popular culture. Yale University Press, 1992, p. 124.

11. Ciarlo, op. cit., p. 289.

12. Tompkins, Kyla Wazana. Racial Indigestion. New York University Press, 2012, p. 29.

13. Cölfen, Hermann. ‘Vom Kochrezept zur Kochanleitung: Sprachliche und mediale Aspekte einer verständlichen Vermittlung von Kochkenntnissen’. Essen im Blick. Ein interdisziplinärer Streifzug (2007): 84-93, here p. 86.

14. Friand, Paul. Notre Cuisine, 1896, p. 203.